hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

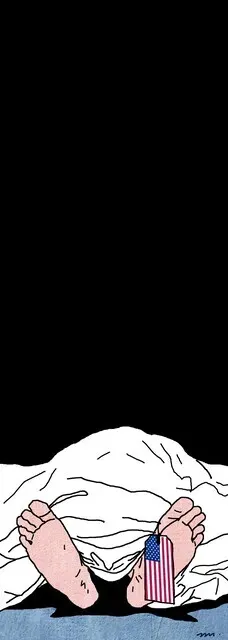

[Column] The world without America

By Pak Noja (Vladimir Tikhonov), professor of Korean studies at the University of Oslo

I recently spent a little over a week in the US. I had some presentations and conferences in different locations, and as I traveled from the West Coast through the Midwest and eastward to New York, I had the opportunity to speak with many residents along the way, including higher education professionals.

Some people tried to dissuade me from visiting the US, insisting that things are troubled right now. But I made a point of going for a simple reason: I wanted to see and understand for myself the nature of the “Trumpism” that is rapidly altering the world’s geopolitical and geoeconomic landscape. I wanted to feel the mood on the ground, which is not something that can be gauged online.

To sum it up, I did indeed achieve what I set out to do. After my journey, I felt like I had some understanding of the implications and context of Trumpism.

What does “Trumpism” mean to people in the US? To begin with, I could sense a tremendous feeling of diminishment in the public sector.

Around 300,000 government employees are already being let go, including around 220,000 probationary employees. That is a substantial number for a country with only 2.4 million federal government employees.

The Department of Education is now being outright abolished, joining the previously scrapped USAID. Workers in the fields of aviation safety, nuclear power security inspections, and national parks are being fired en masse.

Ronald Reagan and George Bush were also neoliberals, but these kinds of massive cuts to the administrative state are without precedent in post-World War II US history. It now appears inevitable that the US will see unprecedented reductions in the areas of education, research, and development, too. The painful reality attested to by many of the colleagues I met in the US was one marked by hiring freezes at universities and the full-scale slashing of research budgets.

In addition to its internal reductions, the US is also undergoing a dramatic slimming down of its external hegemony.

Currently, it is going through the steps to shut down Voice of America and Radio Free Asia, which have been key components of the US’ soft power since the Cold War era. The US military had previously been regarded as sacred, but even there, the number of generals is being cut by around 10%. The Central Intelligence Agency, which has never before been targeted for staff cuts, is now gripped by layoff fears.

In terms of foreign policy, Trump appears to be restructuring both the hard power represented by the military and intelligence institutions and the soft power represented by propaganda institutions.

But even as the administrative state’s scale is shrinking, its oppressiveness is multiplying. In a situation straight out of the first Red Scare of 1919-1920, foreign nationals who have vocally supported Palestine in violation of unofficial US national policy are being arrested and expelled.

The policies of preferential treatment for the disadvantaged and reverse discrimination that have developed since the 1960s are now disappearing. Things have reached the point where those who receive research funding from the state face issues if their publications have titles that even mention today’s taboo words such as “inequality” or “minority.”

As the administrative state shrinks, the national borders are also becoming much more closed off. Tariffs are rising on imports, but it has also become more difficult for people to cross borders. Undocumented workers are being mercilessly driven out, and the US government is now moving to impose full or partial bans on US travel for citizens of around 40 countries.

Once considered a nation of immigrants, the US is now transforming into a society that is as anti-immigration as it ever has been.

These policies by Trump can be summed up as at least a partial return to the past. Specifically, it is the past of the pre-1930s United States — the times before the early welfare state represented by the New Deal and before controls on capital.

In those days, the US had the smallest public sector among wealthy countries, and its taxation rate was extremely low. The federal government provided little in the way of support for education or research.

The US of the 1920s was already an economic power, but its foreign policies were for the most part measures to facilitate US trade and investment.

Though it emphasized trade and investment, the US of the 1920s was also a protectionist and isolationist state. The import tariffs imposed in 1922 averaged 40%, while the Immigration Act of 1924 more or less fully banned immigration by Asians and heavily restricted immigration from southeastern Europe.

At the same time, suppression of political opponents was intense. Radical socialists and others were some of the main targets preyed upon by the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation, the precursor of today’s FBI.

So how does a partial return to the past provide a practical foundation for US national policy? This is a matter that relates directly to the basic character of the US as a country.

South Korean history has, for most the part, been an era of government dominance over capital. In China and Russia, bureaucratic groups hold absolute dominance over business.

The US represents the diametric opposite: a state that is more accurately defined as a tool for business interests. Ahead of preserving external hegemony, the US’ primary reason for existing as a state is the preservation of profit rates for business.

If it is perceived that US hegemony predicated on open trade is now no longer helpful — or even detrimental — to preserving profit rates for US business interests, US policymakers have the potential to put that hegemonic order under the scalpel of restructuring at any time. Should the call be made that laying off civil servants to stanch fiscal spending and reducing interest payments on government bonds is necessary to maintain the status of the US dollar as a key currency, then the military and CIA could be up on the chopping block as well.

In the end, the US is both attempting to sidestep a profit crisis for capital by returning to the era of small government, protectionism and isolationism as it struggles to keep up with China and other newly industrialized countries in the technological and production race, as well as launching a preemptive strike on radicalization that worsening inequality could well engender by stamping out any and all dissent.

Trump is angling to return America to its status as a protectionist economy and isolationist society that can be controlled by the white capitalist elite through exclusion. But doing so certainly doesn’t guarantee that the US will be transported back to its heyday. Tariffs will fuel inflation, while the slashing of aid to education and R&D will only hurt America’s ability to compete with China in the long run. Laying off civil servants, especially those who oversee safety, without any plans for what comes next, could make America an even more backward, more dangerous place than it already was.

But even if Trump fails and he and his ilk lose power, it’ll be too late to salvage a world order that orbited around the United States. South Korea should start preparing in earnest for a world without America.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Constitutional Court must at long last remove Yoon [Editorial] Constitutional Court must at long last remove Yoon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2025/0402/2617435819121664.jpg) [Editorial] Constitutional Court must at long last remove Yoon

[Editorial] Constitutional Court must at long last remove Yoon![[Column] Don’t let insurrectionists gaslight you [Column] Don’t let insurrectionists gaslight you](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2025/0331/1917434093426857.jpg) [Column] Don’t let insurrectionists gaslight you

[Column] Don’t let insurrectionists gaslight you- [Column ] The obscenity of Trump’s ‘hasbara’

- [Column] In the name of Korean democracy, I rebuke Yoon Suk-yeol!

- [Column] A country free from the threat of military coup d’etats

- [Column] The world without America

- [Column] Lessons for Korea from America’s Chinese Exclusion Act

- [Editorial] Fear of far-right violence grows as verdict on Yoon’s impeachment is delayed

- [Column] The defeat of America

- [Column] Standing atop the ruins of Korean democracy

Most viewed articles

- 1Arrests, deportations of US green card holders send chill through Korean community

- 2It’s time Korea prepares itself for a peninsula without the US, expert advises

- 3Yoon’s day of reckoning: Experts predict court will oust impeached president on Friday

- 4Samsung Electronics backed into corner by Trump’s subsidy cuts, investment pressure

- 5[Editorial] Constitutional Court must at long last remove Yoon

- 6Rival parties welcome date for decision on Yoon’s impeachment

- 7What the timeline of a snap Korean presidential election might look like if Yoon is ousted

- 8[Opinion] Is South Korea Again Becoming a Shrimp Among Whales?

- 975% of younger S. Koreans want to leave country

- 10I saw deepfakes when exposing the Nth Room case 5 years ago — the government’s lax response is to bl