Tuning in to freedom: A Northeastern professor’s Cold War memories of Voice of America

Growing up in the Soviet Union, listening to VOA was no simple task for Slava Epstein, a distinguished biology professor.

Slava Epstein, a distinguished biology professor at Northeastern University, grew up in a working-class Russian Jewish family in Moscow.

When he was 11, his father returned from a work trip to the Baltics with a rare treasure: a Spidola — the first mass-produced shortwave transistor radio in the Soviet Union.

Unlike children of the Soviet intelligentsia — a social class of educated professionals, intellectuals, writers, artists and scientists — Epstein hadn’t been exposed to literature or culture early on. But the radio, he says, “opened his eyes.”

“It wasn’t difficult to open my eyes,” Epstein says.

Even as a child, Epstein says he never felt a sense of belonging in the Soviet Union. He imagined himself as a citizen of the world and always believed his time in Russia would be temporary.

With his new radio, Epstein discovered Voice of America and Radio Liberty, which broadcast in Russian. He also picked up a French radio station — a language he had taught himself at age 9 by trying to read about the Apollo 11 mission in a French Communist newspaper.

“Every time I tuned to Voice of America, when the reception was reasonable, there was something festive about it. It was an event. It was like celebrating a birthday,” Epstein says.

Voice of America (VOA) began in 1942 during World War II as an anti-Nazi propaganda tool. Over the decades — through the Cold War, global conflicts and political movements — VOA expanded to provide news in nearly 50 languages, reaching more than 354 million people weekly.

On March 14, President Donald Trump signed an executive order calling for dismantling the U.S. Agency for Global Media, which oversees VOA, Radio Liberty and other federally funded international broadcasters. A federal judge has since temporarily blocked the order.

In the Soviet Union, however, listening to VOA was no simple task. Authorities jammed its signals, blasting irritating noise over the frequencies to block access.

Around the same time, Epstein’s parents bought a small summer home about 60 miles south of Moscow. Determined to improve reception, Epstein built a spiral antenna using radio electronics books. He mounted it on a pole, which he attached to the house, and pointed it westward — away from Moscow’s jamming.

“The point is really how much passion a boy of 11, 12 or 13 had for information from the West was critical,” he says. “I was mesmerized by hearing the words and news analysis.”

Through VOA, Epstein learned about world politics, Western culture and free speech. He was especially fascinated by news on space exploration and the Apollo program — subjects that were underreported or censored in Soviet media.

He says VOA’s fairness in covering Russian events helped him trust its reporting on other parts of the world.

“There was no bias I could detect in [their] coverage of the events in Russia, which built trust to everything [else] they said about places I didn’t know, [such as] USA, Western Europe or Middle East,” he says.

Editor’s Picks

Northeastern global community unites as record-setting Giving Day fuels student clubs, programs and innovation

Northeastern professor leads open collaborative project to understand AI reasoning models

This Northeastern graduate and animator is helping ‘reinvent’ local TV news

How telling personal stories of measles infections can increase vaccination rates

Why ‘The Great Gatsby’ still resonates a century after publication

Each summer, Epstein looked forward to immersing himself in the world he hoped to one day be part of.

His parents and grandmother tolerated his listening, though they refused to participate. But when he began writing down what he heard from the broadcasts, they pushed back.

“My parents lived through Stalin’s years as young children,” he explains.

His grandfather narrowly escaped Stalin’s 1937 purges, only to die in World War II in 1941.

“My grandmother went through all of that as an adult,” Epstein says. “All those experiences scared them to a degree that even when it was mildly allowed to listen to Voice of America, they were afraid.”

While it wasn’t technically illegal to listen to Western radio, Soviet law forbade “disseminating false and fabricated information about Soviet life” and “anti-Soviet propaganda.”

Still, Epstein noticed that his father would secretly listen to news during major events like the Six Day War in Israel.

“He absolutely didn’t want others to know that he was [listening] but he desperately wanted to,” Epstein says.

At 17, Epstein met his future wife at Moscow State University, where he enrolled after high school. She came from an intelligentsia family and introduced him to a world of culture and critical thought he hadn’t previously known.

In his childhood circle, no one listened to foreign broadcasts. But in his new social group, he says, VOA and Radio Liberty were common sources of information.

“We would listen, and we would discuss,” he says.

After hearing the reports, people often reacted with disdain, sarcasm or humor toward the Soviet press, mocking the propaganda and misinformation.

Epstein and his family didn’t emigrate from the Soviet Union until 1988, when he was in his late 30s and already had two children. He delayed applying for an exit visa out of fear for his family’s safety and the real possibility of imprisonment.

“It wasn’t really a compromise with myself … the belief that soon we will be gone from Russia was so strong that we just had to wait,” he says.

During that wait, he completed his doctorate and continued listening to Voice of America — even while working for a year on the remote Kamchatka Peninsula, where the signal wasn’t jammed.

When he and his family finally arrived in the United States, his need for Voice of America faded. But its influence, he says, was profound.

“It played a gigantic role in my development, that’s a given,” Epstein says.

World News

-

Is dual citizenship a resume booster? What job applicants and employers need to know

Is dual citizenship a resume booster? What job applicants and employers need to know -

Devastation from 7.7 magnitude earthquake in Myanmar underscores regional lag in construction standards, regulations, says resilience expert

Devastation from 7.7 magnitude earthquake in Myanmar underscores regional lag in construction standards, regulations, says resilience expert -

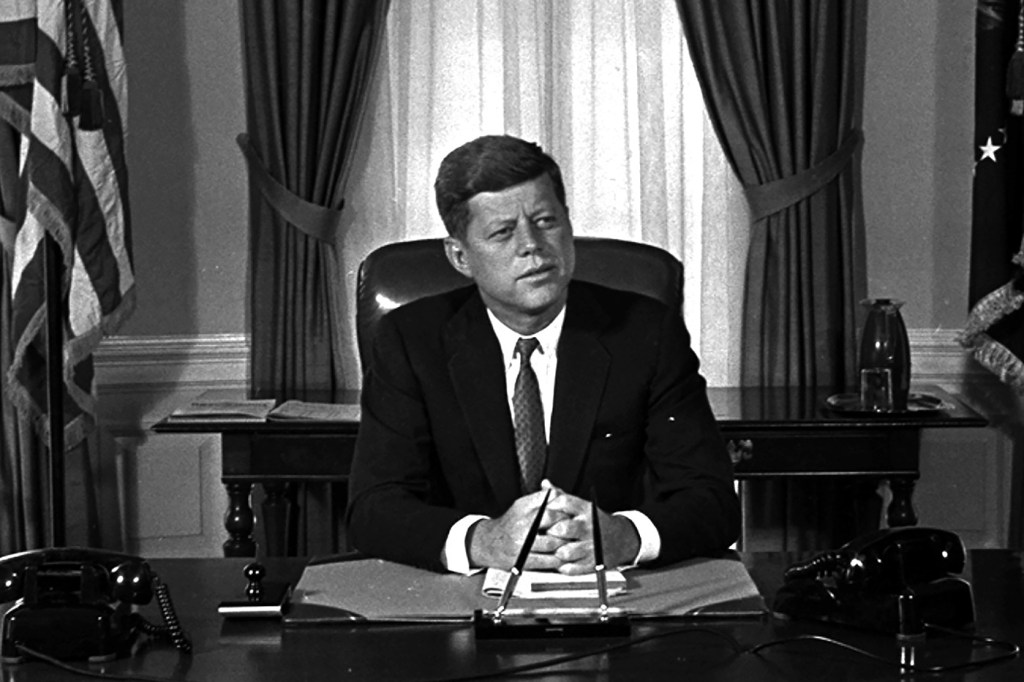

What is in the JFK files? Hear from one historian about whether there were any new revelations

What is in the JFK files? Hear from one historian about whether there were any new revelations