[I]n the tumult of geopolitical history, ultra-nationalist Donald Trump recently held a tête-à-tête with former KGB intelligence officer Vladimir Putin. This month also witnesses the launch of Adamant resident Rick Winston’s book about a previous hard turn to the right in America. Seven decades ago, thousands of people were persecuted for their ties, real or imagined, to communism.

“Red Scare in the Green Mountains: Vermont in the McCarthy Era 1946-1960” will be released by Rootstock Publishing on July 25th. It explores how this once “rock-ribbed Republican” rural state was pulled into the bitter nationwide conflict, how even in Vermont ordinary citizens were seized by an obsessive desire to denounce their neighbors.

In the tiny village of Bethel, for example, the FBI arranged to have the local postmaster intercept mail sent to an influential expert on China named Owen Lattimore. U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy, a Cold War demagogue from Wisconsin, had accused him of being “the top Russian espionage agent in the United States.”

Lattimore and a few colleagues had purchased land in Bethel — Hebrew for “House of God” — for a summer center for Asian studies. They invited a noted scholar from Mongolia known as “the Living Buddha,” and with this added ethnicity component, the smear campaign escalated.

The headline “Vermont Yankees Are Suckers for Commies” accompanied a piece by the Sean Hannity of his day, conservative syndicated columnist Westbrook Pegler. He based the allegation on an interview with Lucille Miller — according to Winston, a Bethel busybody out to expose the nonconformists in her midst. She also targeted nearby Randolph, where some organized labor leaders had vacation homes. Insinuations abounded, rarely based on facts.

Miller wreaked a lot of damage. “I think of her as looking like Margaret Hamilton in ‘The Wizard of Oz,’” said Winston, referring to the character whose nemesis is Toto.

A cineaste who owned the Savoy Theater in Montpelier for 29 years — the last 10 of them with his wife, Andrea Serota — Winston now conducts lectures and seminars on subjects ranging from film noir to crime capers.

His other long-standing passion is music. Via the accordion, he taps into a Jewish folk-jazz tradition with the Nisht Geferlach Klezmer Band. “It literally means ‘not dangerous, colloquially, ‘no big deal,’” Winston said.

Danger was a big deal during his childhood in suburban Westchester County, as a “red diaper baby” born to progressive New York City school teachers involved in union activities. “They were investigated,” he said.

As other citizens plagued by the blacklist turned to alcohol, divorced, left the country or committed suicide, the Winston family managed to remain strong. “I marvel at the lengths my parents went to keep all that away from us. We never knew they were threatened with losing their livelihoods.”

Those grim years under scrutiny were retribution for what numerous Americans did during the 1930s and 40s to advance the leftist dream of better working conditions, better pay, social justice and racial equality.

But there also may have been a sort of cultural high. “My father told me their gatherings provided a built-in social life,” Winston recalled. “I guess the communists had the best parties.”

Then along came the punishment. Winston’s book cites a line from novelist Philip Roth about a generation of idealists who were “impaled suddenly on their moment in time.”

After Columbia University and UC Berkeley, Winston relocated to Vermont. He didn’t grasp the full dimension of his parents’ ordeal until 2011, when he obtained their files from the archives of the New York City Board of Education.

Winston had been trying for more than 20 years to understand how a place that might seem remote from the vicissitudes of anti-communist fervor had, in fact, succumbed to widespread paranoia. “McCarthyism in Vermont” was a 1988 Montpelier conference that Winston helped coordinate. The event opened many doors of perception for him about the Red Scare, among them a realization that it can happen here.

“It Can’t Happen Here” is a 1935 novel that Nobel Prize winner Sinclair Lewis wrote at the Barnard, Vt. home he shared with his wife, journalist Dorothy Thompson. In this cautionary tale coinciding with the rise of Adolph Hitler in Germany, the plot concerns a president with fascist tendencies disguised as patriotism, and a platform for returning to “traditional” values.

The public is in denial, silenced by fear or complicit, though not protagonist Doremus Jessup. He puts out a resistance newspaper, “The Vermont Vigilance.”

When McCarthyism sank its teeth into the likes of Lucille Miller, there were a few ink-stained scribes in the state willing to resist. “A sub-theme of my book is about the terrific Vermont editors and publishers who fought back,” Winston said.

John Drysdale of the White River Valley Herald and the Rutland Herald’s Robert Mitchell found themselves in the thick of the Bethel-Randolph dispute. When Diliwa Hutukhtu, the Mongolian dignitary, arrived to spend a summer in the area, Drydale’s editorial proclaimed that the paper was “proud to welcome a Living Buddha.”

Putney had its own brush with intolerance a few years later. Carmelita Hinton, founder of The Putney School, and her children, were advocates of civil rights and world peace, with a little Marxism thrown into the mix. Two of the children lived in China for a while. The family was labeled subversive by the FBI, Winston writes.

The Putney School was more resilient than the University of Vermont, which succumbed to a right-wing attack on tenured biochemistry Professor Alex Novikoff. His colleagues thought it shameful, Winston learned. Some were brave enough to say so.

Novikoff had joined the Communist Party while a Columbia University grad student in 1935, when that sort of thing was de rigueur. He came to UVM a dozen years later. But by 1953, the academic became “impaled suddenly on his moment in time.”

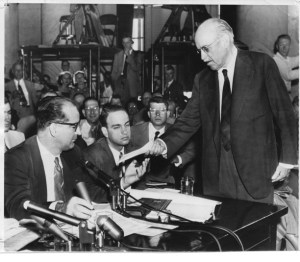

But the country’s mood was changing, albeit slowly. Another Vermonter — Republican U.S. Senator Ralph Flanders of Springfield — introduced a 1954 motion to censure McCarthy. He worried that one result of the Red Scare had been “the loss of respect for us in the world at large.”

A Rutland Herald editorial suggested that Flanders‘ landmark Senate speech heartened the “vast majority of Americans who hate communism but who also revere the Constitution.”

In his chapter describing these developments, Winston includes a quote from Flanders about McCarthy “using his methods to attract attention to himself… unfortunately, because of the kind of person he is, he can’t seem to attract attention without embarrassing other people.”

Winston is keenly aware of the similarities between McCarthyism and Trumpism, yet his outlook for Vermont is guardedly optimistic. “I can’t imagine it happening here again,” he said.

“There has been, since the 1970s, strong support of progressivism,” Winston said. “But it’s definitely not a homogeneous state politically. So, although things may play out differently here than in, say, Kansas or Louisiana, we are not immune to the current nativism and anti-intellectualism. But nativism and anti-intellectualism have long been strains in American life, and they know no borders.”

For the moment, however, “We live in a nice bubble,” Winston said, emphasizing the chronology of his Red Scare timeline, which ran from 1946 to 1960. “In a way, the bubble started for us where the book ends.”